Valuing Flanigan's Enterprises (NYSE:BDL)

A restaurant and package store chain selling under intrinsic value

Introduction

I’ve owned Flanigan’s Enterprises, Inc. (NYSE:BDL) for over a year now. Though the stock has decreased due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its risk profile has increased, I think it is currently selling for less than half of its intrinsic value. As a lightly traded small-cap stock, I think that it’s overlooked. As revenue grows, as it has year-on-year for many years, I think it will attract more attention from the market, leading to the price rising to reflect its intrinsic value. In this article, I want to explain the business and explain how I value it.

Business Description

Flanigan’s Enterprises owns restaurants and package stores in Florida, mostly south Florida. Flanigan’s operates 27 units. These units are restaurants and package stores. In the past, Flanigan’s owned an “adult entertainment club” in Georgia, but they didn’t manage it. They closed it down in 2018 due to a change in the local legislation. Here are the different ownership and management structures they have:

They own 100% of 17 of the 27 units operated.

They have entered into limited partnerships, where they own a portion of the restaurant of the package store, but manage it. 8 of the 26 locations operated are limited partnerships.

They have one franchised location that they manage.

They manage one restaurant that they do not own. ("The Whale's Rib")

Besides the 26 locations they operate, five locations are franchised (and not operated by Flanigan's).

All the restaurants they operate, except “The Whale’s Rib”, are operated under the name “Flanigan’s Seafood Bar and Grill”; all the package liquor stores they operate are operated under the name “Big Daddy’s Liquors”.

They have been operating in south Florida since 1959, running small cocktail lounges and package stores. They expanded throughout Florida in the 1970s. In the 1980s, they expanded to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, but have since closed down all these locations. In 1985, they began franchising their cocktail lounges and package stores. In 1987, they began converting the lounges into full-service restaurants. Over the last twenty years, they have begun using the limited partnership models – in which they operate the store but own only a portion of it – to expand their restaurants. They no longer plan to franchise their restaurants or package stores.

The whole purpose of Flanigan’s Fish Company, LLC is “to acquire and sell only to [their] restaurants imported fresh fish at competitive prices to what we are currently paying outside fresh fish purveyors.”[1]

Understanding the Restaurants

Flanigan’s owns and operates nine restaurants (“Flanigan’s Seafood Bar and Grill”), some of which are jointly operated with a connecting package store (“Big Daddy’s Liquors”). The restaurants are full-service, “neighborhood casual” restaurants. The restaurants serve lunch and dinner, staying open until 1:00 - 5:00 a.m. depending on “demand and local law.”[2]

Franchised Restaurants

Though Flanigan’s Enterprises doesn’t plan to franchise anymore restaurants, they have five franchised restaurants. The franchise agreements require that a percentage of gross sales be paid each week in arrears for (i) a royalty, and (ii) to contribute towards advertising costs. The combined franchise fee works out to between 4.5% and 6.0% of gross sales. The owners of the franchised restaurants are, I believe, related to the executives of Flanigan’s Enterprises.

Limited Partnerships

Over the last two decades, they have opened restaurants through limited partnership agreements. In these arrangements, they join with other investors (often affiliated with members of the company’s executive team or board of directors) to open the restaurants. Flanigan's Enterprises owns anywhere from 5% to 49% of these restaurants, with the rest being owned by partners. So Flanigan's Enterprises can open restaurants while only contributing a portion of the needed initial capital investment.

How do they make money from these limited partnerships? The easiest way to understand it is that they make money for three different things in their limited partnerships:

Income Sharing to the Partners: Since they own part of the restaurant, they get a portion of its net income.

Management Fee: Since they manage the restaurants, they get a management fee.

Fee for Using “Flanigan’s Seafood Bar and Grill”: Since these restaurants use the “Flanigan’s Seafood Bar and Grill” name, they get a fee from the restaurants, in part, I presume, to help cover the advertising expenses for the Flanigan’s restaurants. The fee is 3% of the gross sales, paid weekly, in arrears.

The only confusing bit about this is that they make different amounts depending on how much of the partners’ initial investment is paid back. There are three stages:

Until 25% of the Initial Investment Is Paid Back: The 3% fee is paid, but no management fee is paid. All the net income is distributed to the partners, distributed in amounts relative to their initial investment. (If you invested 5% of the initial investment, then you will get 5% of the distributed cash.)

From 25% to 100% of the Initial Investment Being Paid Back: The fee of 3% of gross sales is paid. Half of the net income is paid to Flanigan’s Enterprises as a management fee. The other half of the net income is distributed to the partners to pay back their initial investment, in proportion to their initial investment.

Initial Investment Is Fully Paid: The fee of 3% of gross sales is paid. Half of the net income is paid to Flanigan's Enterprises as a management fee. The other half of the net income is paid to the partners, in proportion to their initial investment.

Competitive Advantages

The restaurants compete with other restaurants in two general areas: the facilities (location of the restaurants and the quality of the facilities) and the food (the type of food served, quality, and price). The bad thing about this is that there is no moat or barrier to entry. I believe that they can only keep their revenues growing – or at least stable – by keeping their food quality and quality of service high, their prices competitive, and their locations convenient and attractive. So, they do not have a great competitive advantage; all they can focus upon is executing better than competitors upon food, service, and location.

(Though I’ve talked about food quality and prices in the preceding paragraph, I am speaking about all items they sell in their restaurants, including their alcoholic drinks. The latter accounts for about one-fourth of the sales for their restaurants.)

Flanigan’s name recognition and reputation are a critical component of competing with other restaurants. So far, it seems that they continue to have a good reputation in the area. I will discuss this more later, but I have checked the Google reviews of all their locations, and their reviews are positive. So, while there are no barriers to entry and so competitors can take their business, it seems Flanigan's Enterprises is in a good position: they have a good reputation and management skilled at restaurant management.

Understanding the Package Liquor Stores

Flanigan’s owns and operates ten package stores (“Big Daddy’s Liquors”). There are another three package stores that are franchised. Some of the package stores are jointly operated with a neighboring location of “Flanigan’s Seafood Bar and Grill.” The stores are open seven days a week, closing around 9 or 10 p.m. but with a “night window” for extended hours.

Franchised Package Stores

Though Flanigan's Enterprises doesn’t plan to franchise any more package stores, they have three stores that are franchised. The franchise agreement requires the franchisees to pay a portion of gross sales as royalties and a portion of gross sales to contribute to advertising costs. The combined franchise fee works out to about 2.5% to 4% of gross sales, paid weekly in arrears. The owners of the franchised restaurants are, I believe, related to the executives of Flanigan's Enterprises.

Competitive Advantages

The package stores emphasize high volume business at discount prices. They have a wide selection of liquors, beer, and wines, and they compete on prices. In fact, they meet “the published sales prices of [their] competitors.”[3] Their competitive advantage seems to be the price. They have a good reputation, according to the Google Maps ratings and comments, and they seem to have name recognition. Nonetheless, their annual reports make it clear that their main way to beat competitors is mainly by price. Their good reputation helps, but it likely has almost no effect unless they are also competitive on prices.

(It doesn’t seem that they can expand their package stores outside of Florida and keep using “Big Daddy’s” name. A restaurant outside of Florida has registered the trademark “Big Daddy’s”, but Flanigan's Enterprises can keep using that name for liquor sales within Florida. So the expansion of their package stores outside of Florida would be impossible unless they opened the stores under different names.)

Understanding the Management of The Whale’s Rib

Another source of income for Flanigan's Enterprises is the management fee they receive for managing another restaurant in South Florida, “The Whale’s Rib.” They’ve managed this restaurant since 2006. They receive one-half of the net profit generated by this restaurant. In the fiscal year ending on Sept. 28, 2019, they were paid $375,000 to manage the restaurant. This restaurant has good customer reviews (4.5/5.0 on Google) and has generated income for Flanigan's Enterprises for years. In fact, a few years ago, Flanigan's Enterprises and the owners of The Whales Rib explored expanding this restaurant concept to other locations, but they eventually decided to abandon that idea.

So this will continue to generate cashflow for Flanigan's Enterprises, but it is unlikely that this cashflow will increase substantially.

About the Executives

Flanigan's Enterprises is heavily influenced by the family of the founder, Joseph G. Flanigan. His family owns more than half of the company. James G. Flanigan, Joseph’s son, is the current Chairman of the Board of Directors, as well as CEO and President of the company. James G. Flanigan has been the President since 2002, and he’s been the CEO since his father’s in 2005. He owns 20.4% of the company’s stock. The CEO, COO, and CFO have been with the company for over 15 years each, with the CEO and CFO having been with the company for even longer.

I have been able to find out very little about the management. They seem to be loyal to the company and appear to have plenty of experience in managing restaurants. They are conservative in their use of debt and their issuance of common stock, both of which are positive for the investor.

Why Limited Partnerships Work Well For BDL

When I was first researching this stock, I was confused about the limited partnerships. I am still new to business analysis, but I was very, very new to it then. I was almost scared away because BDL seemed to be too complicated. How should one value these limited partnerships?

Even worse, they seemed to be a red flag to me. BDL had a lot of cash, so why didn’t they just open these restaurants themselves, without looking for partners and complicating things? In other words, if a new restaurant was a great investment, why not be 100% of the owner, rather than 5% to 49% of the owner? (I’d rather own 100% of a great apartment building than 50%.)

But I just wasn’t paying close attention to how they were structuring these partnerships. Flanigan's Enterprises seems experienced and skilled at managing restaurants, especially their own concepts. (After all, the owners of “The Whale’s Rib” pay BDL almost half a million a year just to manage that restaurant.) But a new restaurant, especially in South Florida, is expensive to open, even if the building is leased. The leasehold improvements and opening costs are hundreds of thousands of dollars.

But the more I’ve thought about it, the more I’ve realized that these partnerships are a great way for BDL to get a better return on invested capital. After all, they can invest limited capital, as low as 5% of the initial investment, but reap way more than 5% of the net income. After a 5% investment (like they made in one of their Miami locations), they received 52.5% of the net income (50% of the net income as a management fee, and 5% of the remaining 50% of the net income). That’s 10x the return on invested capital they would’ve gotten as 100% owners – and that doesn’t even include the 3% fee on gross sales that they receive. So, these limited partnerships allow Flanigan's Enterprises to get a much higher return on invested capital than they would’ve gotten otherwise.

To show this, let me give an example using some figures provided by BDL and some estimates I’ve made. The average Flanigan’s Seafood & Grill restaurant has annual revenue of $5.5 million. The gross margin for the restaurants is about 64%. After taking out an estimate of their share of payroll and occupancy costs, then applying the 14% tax rate, I calculate that the net income from each restaurant is about 15% of revenue, or $825,000. Finally, it seems that the initial investment for a restaurant is about $750,000.

If Flanigan’s opens a restaurant and invests 100% of the money, and so get 100% of the net income, then they are making $825,000 on the initial $750,000 investment, or a 110% return on invested capital. But, if they only but down, say, 25% of the initial investment, or $187,500, the math changes. If We look at the second phase of the payback, when Flanigan begins to earn their management fee, you can see how the math changes. Here’s how this breaks down:

They get 3% of the gross sales as a royalty, so that is 3% of $5.5 million, or $165,000.

The net income of the restaurant is estimated as the gross sales after removing the royalty fee, or $5,335,000. The net income margin is estimated at 15%, so 15% of $5.335 million is, $800,250.

They get 50% of the net income as a management fee, which works out to $400,125.

They get 25% of the other half of the net income, since they are a 25% partner. This works out to $100,031.

So, their total earnings from this restaurant are $165,000 for the royalty, plus $400,125 for the management fee, plus $100,031 for being a 25% partner. These add up to $665,156.

What is that return on invested capital? They invested $187,500, but made $665,156. That’s a 355% return on invested capital in one year!

Now, even if my estimates are off by a lot and the restaurants are not generating that much net income, you can see that these limited partnerships cause their returns on invested capital to be over three times more than it was otherwise. It certainly seems that the limited partnerships are a great idea when they work out.

Capital Allocation

How does Flanigan’s Enterprises handle capital allocation?

First, they are trying to expand their restaurants. I know of no plans to expand their package stores. Their restaurants are, after all, the higher margins part of the business. But they are looking to expand their restaurants through the limited partnerships, so I think that that slows them down a bit. In fact, they have only opened two new restaurants in the last ten years. So they are slow about opening these restaurants. But it is part of their plan.

Second, they do pay a dividend. They paid a $0.30, $0.28, and $0.25 dividend in 2020, 2019, and 2018 respectively.

Third, in the last few years, they have been comfortable building up their cash and cash equivalents. As of September 28, 2019, they had $13,672,000 in cash and cash equivalents. They have more cash than they have long-term debt. In fact, as of Sept. 28, 2019, they had $7.35/share in cash. I don’t expect them to pay that out as a dividend, so that cash won’t be coming to shareholders’ pockets. But it gives Flanigan’s Enterprises a strong financial situation.

Overall, the management at BDL seems to act cautiously. They do not heedlessly take on debt, and they are not opening new locations at a pace that prevents them from keeping to their high standards.

However, the problem with their capital allocation is that they are so slow to open new restaurants. This means that they are sitting on over $13 million in cash, but they don’t have a good way to put that cash to work. So, overall, their capital allocation would be improved if they could find a way to meaningfully employ their cash. But, since they want to open these limited partnerships

Customer Reviews

I spent one Saturday afternoon reading through many of the Google Business Reviews for each location of Flanigan’s Seafood Bar and Grill and of Big Daddy’s Liquors. Overwhelmingly, their reviews were positive. As of Feb. 2020, their median review for Big Daddy’s Liquors was 4.6 out of 5.0, and their median reviews for Flanigan’s Seafood Bar and Grill was 4.4/5.0. For the restaurants, the reviews regularly mentioned the good service and reasonable prices. Several reviewers also mentioned that the ribs and wings were the best around. For the package stores, reviewers often mentioned the broad selection and the good prices. As I mentioned elsewhere, BDL doesn’t have a moat protecting its profit margins; it has to continue to compete based on quality and prices. Because of that, these customer reviews are important to my assessment of the business, since I can get an idea of how customers are perceiving its quality and prices. And, currently, customers have a positive view of the restaurants and package stores. I have a spreadsheet where I am tracking the customer reviews for each restaurant so that I can notice any decline in customer satisfaction. That would indicate to me that its sales are, at the very least, going to decline.

Valuing Flanigan’s Enterprises

So how do we value Flanigan's Enterprises? I broadly use Aswath Damodaran’s approach to valuation. I know that many value investors dislike Discounted Cash Flows. And I understand their dislike. But, at the end of the day, it enables me to focus my thinking on just a few variables, thinking through what business factors will influence those factors.

The variables I really have to focus on are:

Annual Revenue Growth Percentage: How much will the business grow revenues, on average, for the next five years?

Normalized EBIT Margins: Over the next five years, what will the company’s operating/EBIT margins be?

Sales-to-Capital Ratio: This is the ratio of capital invested (value of equity + value of debt - cash) that is required to operate the business. This is Damodaran’s way of judging the capital intensity of a business, and a way of judging what future investment needs will be.

Working Average Cost of Capital: This is the discount rate at which cash flows are discounted back to the present. I do use the Capital Asset Pricing Model to estimate the cost of equity.

Let me use these factors as a way to discuss the future of Flanigan’s Enterprises.

Dealing with the Limited Partnerships

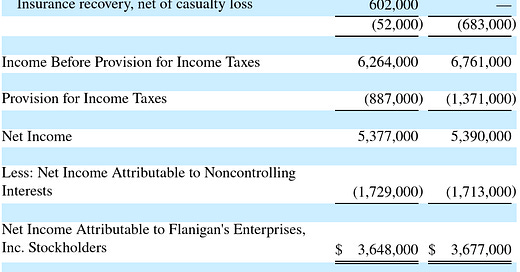

But, first, let me address the limited partnerships. These are, as I explained earlier, a positive for the company. But the revenues and costs for these restaurants get consolidated on the financial reports with all the other restaurants. Then, their portion of the net income is paid to them. You can see how this works in the Income Statement of the most recent 10-K:

I went back and forth on how to account for the partnerships in my valuation. Some people slap a Price-to-Book multiple on the book value of the minority interests (i.e. the amount owned by the non-BDL partners). But the P/B multiples I found to be typical of restaurants varied so broadly that this method led to an absurdly broad range of value for BDL.

So I decided to treat each year’s “Net Income Attributable to Noncontrolling Interests” as an operating expense. I know that it technically isn’t and that this expense fluctuates with the profitability of the company. But this allowed me to look at the cash flow to BDL shareholders more clearly. So the EBIT margins for the company have been adjusted downwards.

Revenue Growth

Quite simply, Flanigan’s Enterprise mainly has two factors that will contribute to its increase: (i) the increase in same-store sales and (ii) building new restaurants. Flanigan Enterprise says in their 2019 10-K that they are not looking to increase the number of franchises, and they do not indicate that they are looking to build new package stores. (As I’ll mention, they are planning to rebuild a joint restaurant and package store that was destroyed by a fire.)

Restaurant Same-Store Sales: In the last 17 years, there have only been three years where the same-store sales didn’t increase for BDL. Two of those years were 2008 and 2009, clearly during the Great Recession. One year was a slight decrease in same-store sales in 2017. I am not sure about the reason for the latter. Some of what I’ve read indicates that 2017 was a rough year for casual dining restaurants; same-store sales were down across the industry, driven by a decline in discretionary income for many Americans and increased competition from meal-delivery services and independent restaurants. When you look over the last 17 years, though, to determine what the same-store sales have been, it works out to a 4% annual growth in same-store sales. I think, then, that it is reasonable to assume that same-store sales will increase by about 4% a year for the next few years. That outpaces the inflation in wholesale food prices, according to the Producer Price Index for the Food, Final Demand, which has shown a 1.7% a year increase in food prices over the last decade. Since BDL’s EBIT margins haven’t improved during this time, it is reasonable to assume that the rest of the increase in same-store sales was absorbed by the increase in labor, leases, and equipment. Nonetheless, I’ll factor in a 4.0% increase in same-store sales for the restaurants in the next five years.

Package Store Same-Store Sales: In the last 17 years, there have only been two years where the package stores’ same-store sales decreased; there was one year where their same-store sales stayed the same, neither increasing nor decreasing. The same-store sales grew at a compounded annual rate of 4.7%. One of the two years of decline was 2008, which is understandable given the recession. Overall, I see no reason not to expect Flanigan's Enterprises to be able to keep growing their package stores’ same-store sales at around a 4% rate.

New Restaurants: According to their most recent annual report, Flanigan's Enterprises is wanting to expand their restaurants through the limited partnership model. As I wrote above, that model helps them to improve their return on invested capital in each restaurant. However, it also seems to slow down how quickly they can deploy the capital, since they have to find partners willing to invest with them. As a result, and perhaps also because real estate in South Florida is so expensive, they have not opened many restaurants over the last few years. So, in my estimations of revenue growth, I did not model any restaurant openings except the ones they explicitly said would open. Over the next two years or so, two new restaurants should open and one restaurant should reopen. The two new restaurants are set to open in Sunrise, FL, and Miramir, FL. Store #19, which was a joint restaurant and package store, was destroyed by a fire over a year ago and will reopen within the next two years. So, in modeling the revenue growth, I assumed that three restaurants would two years. I then assumed that that would increase the restaurant revenues by three times that year’s same-store weekly sales (multiplied by 52 to get us at an annual figure). Then, I assume that these restaurants grow their same-store sales by 4% a year for the next three years.

New Package Stores: According to its most recent annual report, Flanigan's Enterprises does not plan to expand the number of package stores. The only package store that they plan to open is to reopen Store #19, which, as mentioned in the section above, was a joint store with a Flanigan’s restaurant. Both were destroyed by a fire in October 2018. So, in my projections for their revenue, I assume that they will open this package store in 2021. I use the weekly sales for package stores to estimate how much the revenue will increase once this package store reopens.

Other Revenue: Flanigan's Enterprises gets other revenue – though not very substantial revenues – from a few other sources. The only two that really matter are rental income (because they own a strip mall with several businesses leasing space from them) and income from the few restaurants and package stores they actually franchise. I just assume that these continue with the same growth rates as the median growth rate for the last ten years.

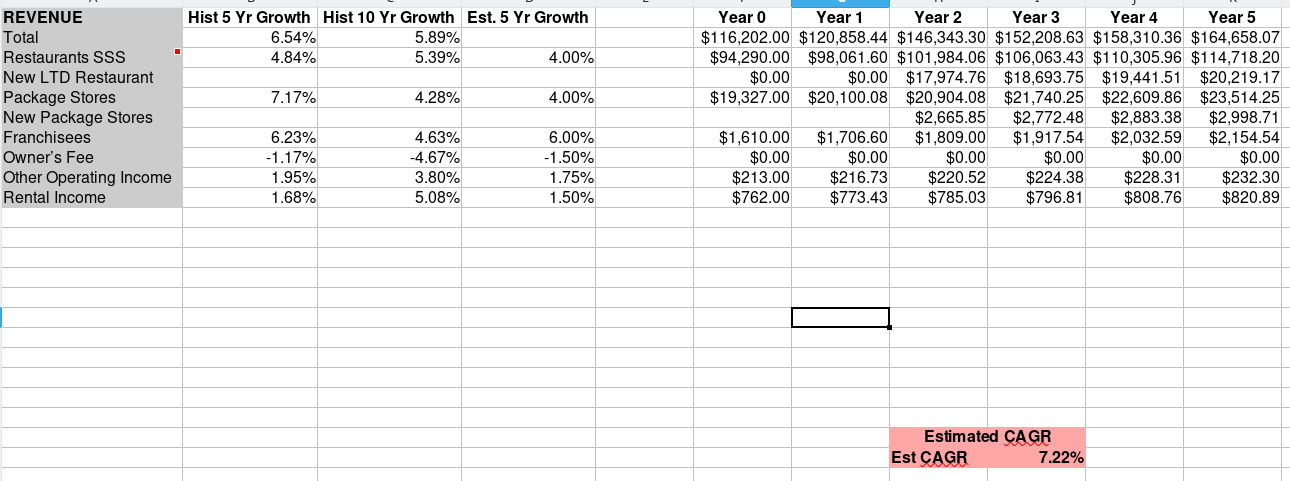

Conclusion: So, what do I think the annualized sales growth will be? Here is a spreadsheet where I projected each stream of revenue forwarded for five years. I then summed those five-year projections to get a projection for total revenue in five years. I then estimated the CAGR of that growth.

As you can see, I estimate that the sales growth for BDL would be 7.22% a year. So, I think it would be safe to assume that revenue growth would be between 6% a year and 8% a year.

Normalized EBIT Margins

To value BDL, I need to determine what its normalized EBIT margins are. The EBIT margins I use are adjusted in two ways. First, as I’ve already mentioned, I take out what BDL pays to its limited partners. On their income statement, this expense is taken out right before net income. But, for valuation purposes, I choose to take it out as an operating expense. Second, I adjust their debt levels for their lease commitments. Since I do that, I add back into their EBIT income the money they paid for rent this year. Why? Because I subtract out their debts from discounted cash flows at the end of the valuation, so I don’t want to account for the lease debt twice (by having them pay their leases and then subtract out what they owe on their leases). So, my EBIT margins differ from what you might see on financial websites and from your own calculations.

Of course, EBIT margins fluctuate from year to year. But for much of the last five years, the EBIT margins have hovered around 6.5%. Also, for much of the last ten years, EBIT margins have hovered around 6%. I see nothing in the business that would lead me to think that the EBIT margins would change much from where they have been the last five years. So I assume that EBIT margins would be somewhere between 5.5% and 7%.

Sales-to-Capital Ratio

Since we are estimating the cash flows the company will generate in the future, we have to determine how much of their operating income needs to be reinvested in the business as it grows. After all, as sales go up, business expenses will likely go up, too.

I use Aswath Damodaran’s approach, and he uses a companies Sales-to-Capital ratio to determine reinvestment needs. This ratio is pretty easy to estimate. The denominator is invested capital, which is book value, plus the book value of debt, plus the future lease commitments converted into debt, and, finally, subtracting out the cash. The ratio is the total revenue divided by this invested capital figure. For the last five years, the sales-to-capital ratio has been around 2.25. I assume that it’ll stay around 2.25 for the next five years. The business doesn’t seem to be changing too much, so I don’t expect this to change. As I argued above, their move to using limited partnerships for their restaurants helps them generate more cash flows with less invested capital, so perhaps BDL’s sales-to-capital ratio will improve over five years. But I’ll assume that it is around 2.25 for the next few years.

Cost of Capital

Finally, I need to estimate their Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) so that I know at what rate to discount future cash flows. With their mixture of debt and equity, I estimate their WACC at 6.66%.

The Effects of Coronavirus

My initial in-depth study of Flanigan’s was done before the COVID-19 pandemic. As a dine-in restaurant business, obviously Flanigan’s has been hurt by the pandemic. They have coped by cutting executive salaries, laying off workers, and taking several million in the PPP loans. Though their intrinsic value has dropped as a result of the pandemic, I still believe Flanigan’s is selling for a steep discount and worth the risk of owning a restaurant in a pandemic.

Though the pandemic continues and so risk remains, I think that Flanigan’s risk is not all that great. First, though their restaurant revenues decline, the revenues from their package stores increased. I have seen several news articles saying that alcohol sales have gone up during the pandemic, and that has been reflected in Flanigan’s financials. Second, they have enough cash to pay off all their debt (excluding operating lease obligations). They are not in immediate danger of being insolvent. Third, their revenues have decreased, but not all that much. It will still be another year, perhaps, before things return to normal. But if their revenues only decline by another single-digit, then everything will be okay. And, fourth, the management responded well to the crisis. They cut executive salaries, laid off workers (unfortunate but necessary under the circumstances), and were able to secure millions of dollars worth of PPP loans at about 1% per annum.

As far as I can tell, the overall impact on revenues has been a decline of 3%. And the adjusted operating margins (adjusting for operating lease expenses and the payments to limited partners) dropped by a third, to around 4%. If we assume that these effects last for a year, then operating margins return to about 6.5% and the revenue growth averages 5% a year for the five years after that.

If you put these assumptions into a discounted cash flow, then Flanigan’s is worth about $38/share. That’s more than double their current price (as of October 29, 2020) of $16.58/share.

(Disclosure: I am long BDL. This post is for informational purposes only. It is not to be construed as financial advice. Consult a professional adviser and invest at your own risk.)

2019 10-K, p. 41

2019 10-K, p. 8

2019 10-K, p. 8